“I’ll Never Put on a Life Jacket Again”: The USS Indianapolis, Jaws, and How to ID a Body

By Sunday, August 5, 1945, there were only the dead left. Three hundred and twenty people had been rescued, the only survivors from the nearly twelve hundred crew members who had sailed from San Francisco on the USS Indianapolis three weeks earlier. The bodies remaining in the water were in such a state of decomposition that many weren’t more than skeletons and skin, barely held together by the straps of their life vests.

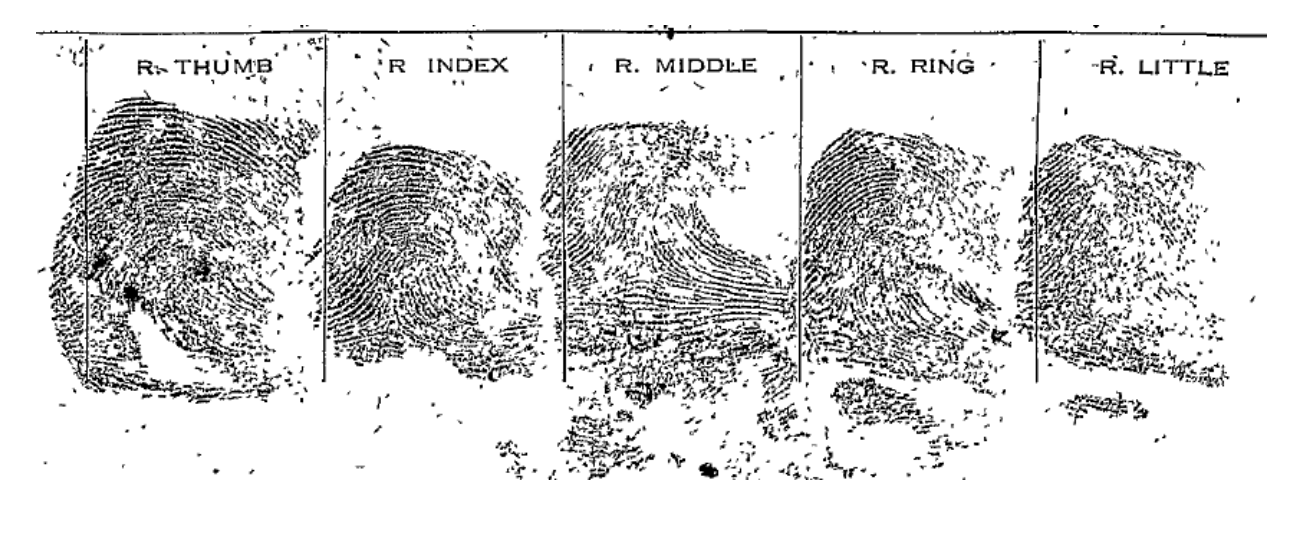

The USS Helm, one of the rescue and recovery ships, noted in its log that faces were impossible to recognize, and most of the remaining skin on the bodies was so bloated, lacerated, and bruised that the Helm’s medical crew could only peel what skin they could off the hands of the dead to take below deck and dehydrate -- the only way to get legible fingerprints. These partial, mangled markings were how many of the bodies were finally formally identified, cross-referenced with Naval intake forms. By the time the sun began to set that Sunday evening, the Helm had already hauled in 18 bodies. They would bring in ten more before ending their mission on account of darkness, but at 7:40PM, according to the ship’s record, they hauled up Body 19.

That was my grandfather.